The oldest known descendant from whose first name is known is Giovanni Embergher and it is assumed that he came from Valcomino. He was the father of Pietro, a wood craftsman who came from a village east of Arpino named Alvito to work as a cabinetmaker in the famous Abbey of Montecassino. Pietro Embergher married Maria Ciccarelli and she gave birth to four children of which Luigi Embergher was the second in row. Luigi Antonio Embergher was born on the 4th of February in 1856 in Arpino. His older sister was called Emilia Domenica Michela (28-2-1851) and his younger brothers were named Allesandro (19-1-1859) and Giuseppe (31-5-1862).

It seems that roots of older descendants of the family are traceable well back into the 18th century, in the village of Tirolo in the north of Italy. This of course explains the somewhat unusual name Embergher and it can be assumed that this is because the Embergher family has its origin in the North of Italy /Austria. During his childhood Luigi Antonio (his Christian name) showed great musical interest as he devoted himself to study plectrum instruments.

His choice for a living was however to follow his father’s footsteps working as a wood craftsman making fine wooden tools and machinery needed in the wool industry. This industry had been flourishing in the Frosinone area since the 17th and 18th centuries and had brought great prosperity to the people of Arpino who nearly all were related to this sector. Unfortunately, due to economical crisis and political reasons, the wool industry had vanished almost completely in the last quarter of the 19th century and many of the inhabitants of Arpino were forced to leave the town to go and find work elsewhere. As so many others from southern Italy, many of them emigrated to Northern Europe and America.

Luigi Embergher stayed in Arpino working as a fine woodworker. It is believed that his profession brought him to Rome and that during this period he also spent some time as an apprentice in a string instrument atelier.

Very soon afterwards he came to work as a luthier in the musical string instrument atelier that his own family had founded at the ‘Vicolo Morelli’ (the Morelli alley). This explains why the Embergher firm named: ‘Fabbrica Strumenti Musicale a Corda / Casa Fondata nel 1870 / Arpino (Frosinone)’, as can be found on some of Domenico Cerrone’s labels, could have been operating as early as in 1870. Often, in earlier writings it is stated that Luigi Embergher was the founder of the Embergher firm, but this seems unlikely since Luigi would have only been 14 years old in 1870! It’s also known via oral tradition by workers of the atelier that Luigi Embergher took over the Arpino workshop around 1880. By then of course the firm name ‘Embergher’ was already established and well-known.

That Embergher sold his instruments in this early period of production either through his atelier or in a shop some where else in Arpino is certain, since the two oldest known instruments, both mandolins made in 1888 and 1889, have printed labels with the following text: EMBERGHER LUIGI / COSTRUTTORE D’ STRUMENTI ARMONICI / ‘Arpino – Via Marco Agrippa N. 26’. This is the first known label with the name Luigi Embergher on it, referring to him as an independent luthier.

Evidence that Luigi Embergher expanded the business with an outlet in the centre of Rome some time after 1889 is retrieved from preserved mandolins labelled with a Roman address. The first musical instrument house, known under the name ‘Casa Embergher’, was located at the ‘Via dei Greci No. 21’, as is proved by two mandolins build in 1894 and 1895. The first instrument is a mandolin N. 3 and the second is the highest artistic model which shows the follow text on the label: ‘Aloisi Embergher, Fecit in Roma MDCCCLXXXXV, Via dei Greci No. 21’.

Instruments that stem from 1897 and 1898 all carry a new manufactured label with, what is likely to be the address of 2nd Roman shop; the ‘Via Tomacelli, 147’. A mandolin and a mandola made in 1898 and labelled with jet another new printed label, point out that the shop in that year must have been changed to ‘Via Dogali N. 10 – 12’. Other addresses of Embergher’s Roman stores are, in chronological order: ‘Via Leccosa N. 2,’ operating as such in 1903 and 1904; the shop at the ‘Via Delle Carrozze N. 19’ address, open from 1906 up to at least 1914 and, last but not least, the Embergher musical instrument house located at ‘Via Belsiana N. 7’ that, although with some periods of closure, was open from 1915 to 1960.

Embergher’s instruments quickly became popular as being the finest in quality and sound and soon many great Italian mandolinists performed on his instruments. Elsewhere in Europe his fame was spread through the activities and concerts of travelling Italian virtuosi that played his instruments. The demand for his soloist models was growing rapidly. This led to the necessity to engage other musical instrument makers and young apprentices to work in the Embergher atelier. One of them was Domenico Cerrone, a very talented young boy who was born in Arpino on the 24th of Januari 1891 and who started to learn his craftsmanship from Luigi Embergher when he was only eight years old. Already at the age of fourteen he was appointed by Embergher as a first class luthier.

Now the demands could be met and the export to foreign countries like Denmark, Belgium, England, Germany and even Russia, India and South America, began. In the twenties the instrument production was at its peak giving jobs to about 15 co-workers and apprentices. The Roman mandolins from the Embergher atelier were regarded as the finest instruments because of the modifications and improvements Luigi Embergher had introduced. Especially the concert-models became, because of their bright and sonorous sound, the perfect intonation and the fine playability, much sought after.

Besides the mandolin the Embergher atelier manufactured all other instruments of the Mandolin family like the terzino, mandola, mandoloncello, liuto cantabile and the mandolbasso. Also of great importance was Luigi Embergher’s creation of a quartet that consisted completely of plectrum played instruments. The first quartet named ‘Quartetto a Plettro Sistema Embergher’ consisted of, as is learned from catalogues, advertisements and editorial writings in mandolin magazines of the time, two mandolins, a mandoliola and a luito cantabile. The liuto cantabile is a 5 course instrument tuned C – G – d – a – e’ and in fact a mandoloncello with an extra highest course tuned to the same pitch as the mandola’s first course. Indeed two instruments in one.

Later, like with the terzino mandolin, the liuto cantabile was more or less taken out of production and replaced by the mandoloncello. The Embergher quartet now became known, because of the similarities with the string quartet, as the ‘Quartetto Classico a Plettro’. One of the finest quartets ever must have been the one lead by G. Burdisso of Rome. His quartet performed on 5-bis concert models and from what is known about their concerts, this combination of high quality Roman concert instruments must just have been fantastic. The ‘Quartetto Classico a Plettro’ was heard for the first time in Rome in 1897 and displayed at the exhibition of Turin in 1898. Besides Burdisso’s classical quartet there was another well-known plectrum quartet which was founded in Brussels by Silvio Ranieri.

Embergher was a gifted master of his art and much concerned with tradition and style. He must have known and studied the old instruments of the Mandolin family and the work of his direct predecessors, since many aspects of early Roman instrument making can be found in his instruments too.

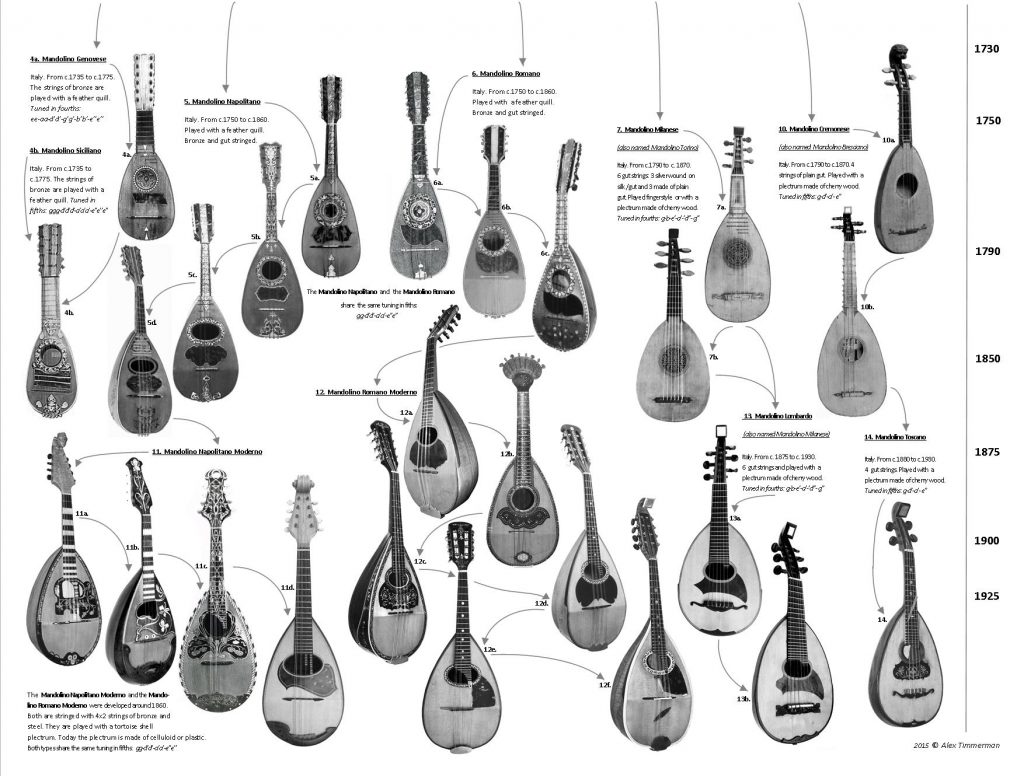

Through the ages the mandolin and its history have been very much associated with Rome. Important developments nearly always originated in this city. The oldest surviving and dated instrument for example is a small gut-strung mandolino made in 1681 by Matteo Nisle, a musical instrument maker who lived and worked in Rome. It was originally designed to carry three pairs of strings and one high ‘chanterelle’. It is now preserved at the Musikhistorisk Museum and Carl Claudius Sammling in Copenhagen.

Later Roman examples made in the first half of the 18th century are the beautiful gut-strung mandolinos by the Roman luthiers Giovanni Smorsone (act. 1702-1738) and Benedetto Gualzatta (± 1668 – after 1742). The instruments by these makers build around 1725 show, through the addition of one extra low string pair, that new developments first took place here. These innovations quickly lead – some ten years later – to the final design of the mandolino: an instrument strung with six pairs of gut-strings which were tuned in unisons like: g-b-e’-a’-d”-g”. This gut strung mandolin type was mostly played finger style or, towards the end of the 18th century, stroked with a wooden plectrum made of cherry wood-waste.

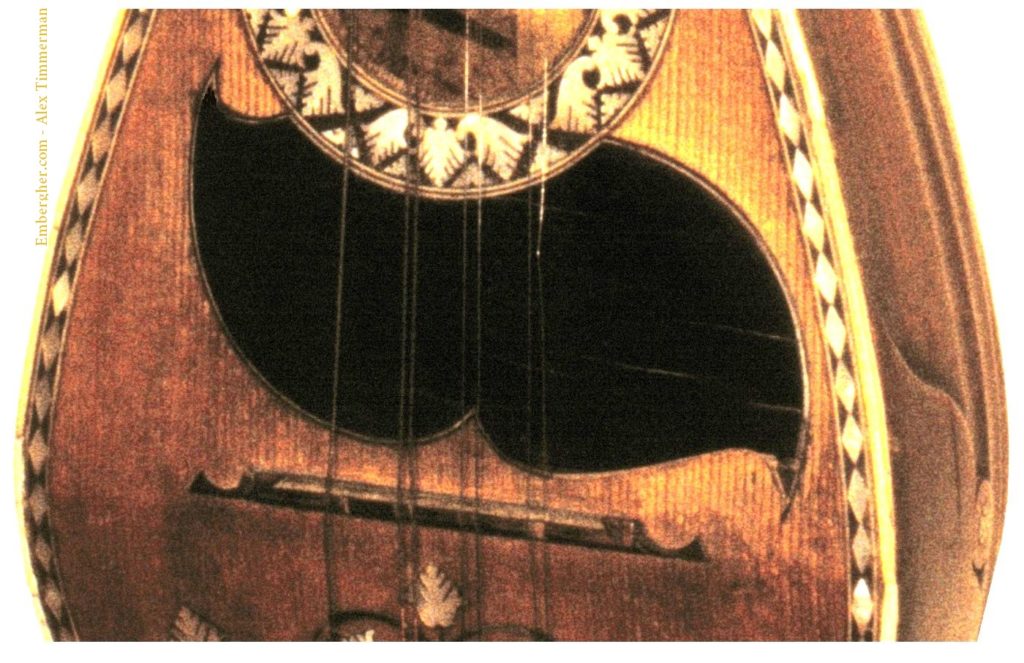

Of note is that already at that time a distinction in design between Roman mandolinos and other Italian mandolinos, can be seen. The sound table of the Roman model is much more ‘in line’ with the fingerboard and always eye catching straight downwards to the broadest width of the sound table. Characteristics that can also be noticed in the excellent work, some thirty years later, by another Roman luthier of importance named Caspare Ferrari (act. 1716-after 1776). Of interest also is that he built both, the older gut-strung mandolino as well as the new metal-strung mandolin type.

The strings of the last mentioned type were – like the modern mandolins of our time – tuned in fifths: g-d’-a’-e” and unlike the mandolino, played with a quill that was made of a bird’s feather. Ferrari’s instruments date from 1731 up to ± 1770 and include several types of the mandolin family, guitars and bass mandolins. Ferrari’s Roman mandolins are comparable with the first Neapolitan mandolins made by his Neapolitan contemporaries Gennaro (act. ± 1710 – ± 1788) and Antonio Vinaccia (act. ± 1734 – ± 1796). They only differ because of the more compact appearance and the straight ‘shoulders’. Eye-catching is also the diagonal designed ‘Roman’ scratch plate, a peculiarity that is also found on Roman metal-strung guitars of the time, and through which Ferrari’s Roman mandolin design distinguishes itself from other metal strung mandolins.

Striking is also that the idea of the slightly curved fingerboard, a typical characteristic of the later Modern Roman mandolin as designed and World patented in the last quarter of the 19th century by Giovanni Battista Maldura (act. ± 1880 up to 1903), that was already seen on some of Ferrari’s mandolins. Features that were applied by Giovanni De Santis (21-XI-1834 – 24-II-1916) in his plectrum instruments and later also by Embergher and his successors in their instruments of the mandolin family,

When these early features of the Roman mandolin are compared with the modernised early versions made by for instance the one of the finest Roman Makers Cav. De Santis, one can speak of a tradition and a fine Roman style of mandolin making. Not much is known about Giovanni De Santis, except for that he learned the musical instrument making craft in the ateliers of Paulo Alessandroni and that he was send abroad to complete a traineeship at the famous Erard pianoforte atelier in Paris. Before making the instruments of the mandolin- and guitar family De Santis made and restored pianofortos, harps and violins. Two Roman atelier locations are known; one at the ‘Via del Quiriale 52’ and a second one, as found on a label in a mandolin made in 1894 , at the ‘Via della Cordonata 28A presso il Quirinale’. De Santis was succeeded by his son Alberto (1876) who, together with his nephew Auguste, operated under the name ‘Figli De Santis’. They were later joined by Alberto’s son Renato (b. 1901).

Besides being a well-known Roman mandolinist Giovanni Battista Maldura was a mandolin- and guitar maker who worked in close collaboration with Giovanni De Santis. Their improvements include the Roman headstock with metal tuning devices placed at the side of the head, the reinforcement of the ribs of the sound box with a thin layer of wooden strips; the ‘V’ shape of the neck, the introducing of a curved bridge and the adoption of a raised, curved and extended ebony fingerboard with 25- up to 29 frets. The curved shape is not the only novelty that can be seen in the fingerboard design. While fret placement on all observed De Santis mandolins is consistent, it is different from fingerboards applied by most other contemporary makers. These differences are especially notable from the 10th through 25th (or 29th ) frets. Interestingly, fret placement on the fingerboards of Embergher mandolins is identical to those that I know by Giovanni De Santis. Also of importance is that Embergher, the Cerrones and Pecoraro, as is proved by their mandolins, never changed this particular characteristic of the Roman mandolin. It is my belief that De Santis, as a trained violin maker, applied this different fret placing to intonate the notes in the highest positions in a more accurate and practical way. It is a departure from the rule in the plucked instrument making field, but in fact very similar to what violinsts do when playing in the highest register of their instrument; they intonate slightly sharp, to retrieve a better, more brilliant sound.

Noteworthy is that the idea of the curved fingerboard and bridge was patented as is shown through the text ‘BREVETTATO DI TASTIERA E PONTICELLO’ printed at the labels of survived mandolins made by De Santis. A label found in a 1894 De Santis mandolin, also gives more insight in the time when the improvements had first been recognized as important, since it mentions that the first specimen of the ‘Mandolino Romana’ had been awarded with a gold medal: ‘PREMIATA CON MEDAGLIA D’ORO ALLA 1A MOSTRA DI ROMA’. The label also reveals that De Santis was honoured with a silver medal at the 1885 Paris exhibition, while in 1884 he had already been awarded with the silver and bronze medals of the ‘Esposizione Generale Italiana’ in Turin. Research has produced evidence that in fact the patent ‘BREVETTATO DI TASTIERA E PONTICELLO’ was owned by Giovanni Battista Maldura and that he inspired Giovanni De Santis to build mandolins to his specifications. Another mandolin prizewinner at the 1884 exhibition was the musical instrument maker Enrico Tacconi. Besides a handfull mandolins and a mandola nothing is known about this Roman luthier. Another Giovanni De Santis mandolin made in 1904 bears a new printed label that shows, next to the previous mentioned medals of Paris and Turin, new gold medals won in Rome (1890), Palermo (1891) and Milano (1894) the medal insignia of the knighthood of the Order of the Italian Crown. All these honourable distinctions point out the importance of Cav. De Santis and that the modernising of the mandolin took place in Rome during the early 80-ties of the 19th century.

After De Santis and Maldura had modernised the mandolin it was generally accepted by most of Italy’s leading performers as the ‘Mandolino Romana’ and the highest developed type within the mandolin family.

Embergher, who in the early 1880ties likely had learned the craft of mandolin making in the atelier of Giovanni De Santis and who with certainty knew Giovanni Battista Maldura, would around 1900 refine the modern Roman mandolin design with the adding of a zero-fret, the extension of the fingerboard under the 2nd string up to the g”’, and the much more pronounced ‘V’-shape of the neck. Refinements that, together with important alterations inside the sound chambers’ construction and strutting of the soundboard, would quickly prove to be of great importance. With the declining activity of the De Santis atelier and the absence from 1903 onwards of Giovanni Battista Maldura, it did not take long before Embergher himself was the prize winning luthier at exhibitions and the only luthier of whom was said to be the best maker of the modern Roman mandolin. A list of medals and other honourable distinctions was printed in his catalogue (printed ± 1926).

Embergher was always concerned about the high standard of his instruments. This is something that is quite noticeable in all his instruments. Besides the high quality his aim was to improve the instruments’ playability and its possibilities. One such an improvement was the creation of a special enlargement under the 2nd string of the fingerboard on the 5-bis mandolin model. Through this extension the 25th fret could be broadened in order to produce the a”’ tone on the 2nd string. The oldest example with this fingerboard that I know of was made in 1915. The idea corresponded with Embergher’s wish that the entire violin repertoire could be played on this soloist mandolin model. In the past virtuoso mandolinists like Silvio Ranieri and Hugo D’Alton played on concert mandolins with this modification.

As mentioned before, Embergher wasn’t only celebrated abroad: His mandolins were praised by teachers of the instrument, professional performers and soloists in Italy, as well for their playability and high quality of sound as for their artistic and elegant design. Because of his successful career Embergher was knighted in 1913 as ‘Cavaliere della Corona d’Italia’ (Knight of the Order of the Italian Crown).

In the outward appearance of his instruments Luigi Embergher maintained the tradition of Roman mandolin making; the headstock of the gut-strung mandolino, the typical diagonal scratch plate and the curved fingerboard like those on Ferrari’s early Roman mandolins.

Besides this, Embergher introduced important innovations inside the sound box to improve the quality of sound. Together with a careful ‘teardrop’ design of the sound box the improvement of the volume was obtained through positioning bars in a diagonal manner onto the sound table. A design created to render as many sound waves as possible on the lower part of the sound table. The strongly build sound box was veneered with wood to keep the ribs of the belly together. Something very much in contrast with the work by Embergher’s Neapolitan contemporaries: the master luthiers Nicola (1859-1924) and Raffaele Calace (1863-1934) who reinforced the belly of their instruments with (wall) paper. To preserve the clear and full sound which is known of the late 19th century Neapolitan mandolins made by Pasquale Vinaccia, Embergher kept his sound tables very thin, only strengthening them by gluing sound bars in a special lute-like way on to the sound table. By using top class wood and other high quality materials like for instance ivory, bone and a silver-nickel alloy (German silver) Embergher developed mandolins with a strong, sonorous warm sound and a perfect intonation that was much appreciated by many great mandolinists of his time.

During the late twenties the Embergher atelier was hit hard by the political regime. This situation led to the limitation of the number of workers at the atelier to only few. In the early thirties Benedetto Macioce, one of Emberghers chief operators, carried on the production of instruments.

In 1935 Embergher decided to close the shop, while the production of instruments continued in the atelier. During this period it is believed that Domenico Cerrone worked on his own as a musical instrument maker in Arpino making guitars and the instruments of the mandolin family after the finest Embergher specifications. On the 16th February of 1938 he decided to officially appoint Domenico Cerrone as his successor. Embergher was then 82 years old.

Photos kindly provided by Ermanno Zappacosta.

With Domenico Cerrone the production of the Embergher line was prolonged with the same artistic skill and acoustic refinement as before. The line of offered instruments even expanded with the fabrication of guitars and violins after the Stradivari model. The main export country during the first 10 years under Domenico Cerrone was Germany.

Luigi Antonio Embergher died in Rome on the 12 of May in 1943.

(1891 – 1954)

Domenico Cerrone was also a founding- and active member of the National Association of Italian Luthiers. His instruments, including the ukuleles and several guitar types, obtained prestigious acknowledgments in the ’15e MOSTRA MERCATO NAZIONALE DELL’ARTIGIANATO’ exhibition of Firenze in 1951 (gold medal); the ‘Secondo Concorso Nazional di Liuteria contemperonea’ of Rome (diploma d’onore); and the ‘Mostra Nazionale de Liuteria Moderna’ Ancona in 1957 (posthumous silver medal).

Besides making musical instruments Domenico Cerrone seem to have been a fine musician for he is remembered as the conductor of several choires and the orchestra of Arpino. In most of the instruments of the Mandolin- and Guitar family, made under the supervision of Domenico Cerrone, the Luigi Embergher ‘Via Belsiana N. 7’ label is found. Sometimes Cerrone wrote his signature on this label too. Also other Cerrone labels carry written additions in ink like the words: ‘Domenico Cerrone e Figlio’, ‘Allvo e’ and ‘violini’. Besides the well-known Belsiana address 7 other printed labels of Domenico Cerrone are known to me.

In 1954, after Domenico’s death on the 21th of November, his son Giannino (b.15-6-1924 – d.1993) succeeded him. He was joined by his nephew Pascuale Pecoraro and Loreto Ranaldi (b. 1935). It would be the last period of activity of the Embergher atelier, since in 1960 the atelier in Arpino and the shop in Rome at the ‘Via Belsiana N. 7’, closed its doors for good. The shop at ‘Via Belsiana N. 7’ had been part of the Embergher firm since the earliest known mandolin (a student type B) labelled with the Belsiana address, was sold there in 1915. It has been acknowledged that most of the instruments of the Mandolin family during this last period were made by Pascuale Pecoraro who, together with Giannino Cerrone and Loreto Ronaldi had learned the craft under Domenico Cerrone. It is also stated that Pecoraro, a gifted luthier as well, worked during the last years the atelier was led by Embergher, worked under the guidance of the maestro himself. Giannino Cerrone was, besides being concerned with running the business, also successful as a (guitar) string maker and a luthier as can be proved by the quality of his ‘Embergher’ mandolins. During the 1955 “Concorso di Liuteria Contemporanea” in Genova he received an honourable acknowledgement from the jury about the mandolins that were sent in for the competition: because of their unsurpassed standard the instruments were place outside the concourse.

Later Pasquale Pecoraro (1907 – 1987) would go his way, and up to in the eighties, continue making fine Roman instruments and although he permitted himself some liberties in the overall design, his mandolins have always been regarded as Embergher mandolins. Some labels in Pecoraro’s instruments reveal that he worked in Rome at the ‘Via Francesco Bonabede 279’ and at the ‘Via Fransesco Secondo Beggiato No 5.

It is also known that in the 60-ties Pecoraro sold his instruments through a musical instrument outlet in London, with the following address: ‘104, Venner Road, Sydenham, London, S.E.26, England’. This address appears on an additional typed label in the mandolins made during that period. At that time Pecoraro also published a catalogue for the English market written in the English language. In it he describes his mandolins, in the same order Embergher did, ranking from study types and orchestra models up to the number 6 model for the virtuoso and concert artists. Curiously he adopted a written homage to the catalogue celebrating the Mandolin, its makers, its composers and its most famous players of the past, informing the reader as follows:

(1907 – 1987)

Historical Note

“During the first decades of the 19th century, the legendary Niccolo Paganini, astounded and inspired, composers, artists, and music lovers, with the wonder of his playing.

Not least among these were the Mandolinists of the day, who endeavoured to emulate him on the Mandoline. Unfortunately their instruments were totally inadequate in range and power to satisfy this demand, in consequense of which they importuned the Luthiers to design superior instruments. Happily there was such a man of vision ready for the challenge, one Pasquale Vinaccia of the celebrated family of Luthiers in Napels. His genius was to raise the mandoline from a purely Folk instrument, to the concert platform, and the Orchestra, and inspire succeeding Luthiers to give the instrument resources and beauty, second only to the Violin.

Today we have the written records of such a proud achievement, in the music of such renowned masters as the Fabulous – Calace – Munier – Arienzo – Marucelli – la Scala, to mention but a few of the pioneers, not forgetting those that followed even to our times.

In the latter decades of the Century the virtuosity perfected was such, as to demand further improvements to the instrument, again Luthiers of stature rose to the occasion. Such men were Embergher and de Santis of Rome, whose genius has given us the Modern concert Mandoline, designed to sing with the sweetness of a Prima Donna.

For the violin in voice and form is Lord, and the Mandoline worthy Consort, in grace, beauty, and charm of voice.

Today these master craftsmen are no more, but happily they passed on their Arts and enthousiasms, for our enjoyment.

Let us give tribute, and discover them.

Pasquale Pecoraro London, anno. 1963 104, Venner Road, Sydenham, London, S.E.26, England.

The Roman Mandolin and its place in the History of the Italian Mandolin